[Editor’s note: My apologies for the poor quality of the light in many of the pics which follow. That’s because it was dark. VB]

By midnight, Caledon was asleep or otherwise amusing itself in private. At any rate, it wouldn’t be taking much notice of me. By then, I’d snatched a couple of hours’ sleep – I would have expected trouble getting off, after the misadventures of the day, but Mr Whybrow’s unscheduled outing had anaesthetised my mind and I drifted off with memories of the Penzance Inn sailing around in my head like a merrygoround. Fortunately, I’d taken the precaution of borrowing the alarm clock from Mr Whybrow’s office.

Before I changed, I gathered up a few items which I expected to find useful. I had already considered the problem of what to wear in London. Traditional female garb would be out for what I had in mind, but I would have to blend in. Londoners were up and about at all hours, and this was one activity for which my shop wardrobe was unprepared. My old workhouse clothes would have been ideal, but Mr Whybrow had sent those back on my arrival here – apart from the boots, which, for some reason, they did not want back. However, some of Uncle Arthur’s old clothes would serve admirably.

A thick jumper would hide my feminine curves, and by tucking his trousers into his socks – a necessary precaution on a motor bike – in the poor light, provided that nobody looked too closely, I believed I’d pass as a young male, even if it was a somewhat effeminate one. I had acquired a sporting air. Finally, to round off the whole disguise, a flat cap. A LOUD flat cap. It would not be sufficient to hide all of my hair, but in those early days of motorbikes, every rider wore them. I would blend in perfectly. The fact that I represented a fashion disaster which would have brought Miss Creeggan out in fevers and boils was only a minor consideration.

I checked over the Dreadnought as per Mr Whybrow’s advice, but found nothing amiss. But then, those two would have to have been pretty foolish to try interfering with the bike again, so soon after previous attempts had failed. After a warm evening, the four dear little spark plugs caught immediately, and vaulting into the saddle, I eased the throttle wide open and headed out of Caledon. I didn’t bother with the headlamp; the moon silvered the streets while making an untidy ghost of shopgirl and Dreadnought as I throbbed northwards. I’d already been looking forward to this night as a change from the stresses of the day, it now thrilled me as I imagined a seaside outing might, a child. And even Jasper could not follow me to London.

I was also more settled in my own mind about Mr Whybrow, now that I’d had time to sleep on it. I think I knew how he saw me. As a companion. As for romance, he was sufficiently confident with women to make his feelings known, if they were there to be made known, and was sufficiently in control of himself not to risk the world he had built for the sake of a relationship which, to judge from his experience, would only leave him sitting on his fundament. But there was no denying that those two villains were drawing Mr W and I closer together.

Then so be it. I’d learned to be happy with his company in just about any circumstances, and he valued mine without trying to force himself upon me. I was happy for life to continue without any deeper sort of bond developing between us, as I’d found so much to fulfil me as things stood. But if I should ever devote my life to an individual, no better candidate was in sight.

Let it stand, I concluded, Whatever happens, happens. Either way, you can’t lose. But now it looks as though you’ll have to fight for it.

On reaching the outskirts of London, the first thing I had to remember to do was to switch the headlamp on. The second was to slow down. I couldn’t remember what the speed limit was, although I do remember that the government had recently done away with that silly requirement for a man with a red flag to precede a self-propelled vehicle. But here, I could take no chances. I would only pass as a male motorcyclist at a casual glance; if a policeman pulled me over, I’d be in more trouble than I could talk myself out of.

The West End was as busy as I’d expected it to be, thronging with theatregoers wending their uneven way home after post-performance night caps, and ladies of the night reeling in drunken servicemen, but I scarcely stood out. It was a little unnerving to wind myself around wagons and carriages, even though my manoevrability and braking were infinitely better than theirs. I’d forgotten to allow for the cruddy fog that descended as the night cooled, but that I was happy to live with. The air made my chest tighten, having lost my tolerance to it in Caledon’s wholesome atmosphere, but it helped me maintain my anonymity.

It was an odd feeling, though, as I purred along High Holborn as smoothly as the night traffic would let me. I was returning as a woman of some substance, but not in that guise. I had to shake my head a couple of times, as that peculiar feeling of being separated from myself and the world tried to wrest my concentration.

I judged it better to leave the Dreadnought in plain view, but just off Gray’s Inn Road. There were plenty of dark alleys where it would not be seen from the street at all, but those attracted the very individuals whom I would not want to find the bike. As an additional precaution, I removed the rotor arm although I doubted that many in London would be able to start the bike anyway, even if they knew how to.

Despite having spent most of my time there in near-incarceration, I knew Central London well. I’d planned my route carefully. I’d parked near a side gate that was used for loading, and for removing the deceased. It was only openable from the inside, with any arrivals having to report to the main gate which, even at this time of night, was staffed. However, the side gate was not. But first I had to get inside, which I had foreseen. Mr Whybrow had, as I’ve already mentioned, removed as much of Old Stumpy’s rigging as was possible without the masts blowing down, since the ship wasn’t going anywhere and one never knows when half a mile of assorted line will come in useful. The addition of a crowbar to thirty feet of rope procured my way in.

In the feeble gaslight’s upper reach, I barely stood out against the wall as I hauled myself up, and was swallowed entirely by the shadows when I descended the other side. The cellar door was stoutly locked as I remembered; without that precaution, it would have been commonplace for the establishment to lose half a ton of coal overnight to the locals, or any number of other assets, with galvanised buckets fetching fifteen shillings a hundredweight. The lock was too heavy for me to pick, or break without making a noise. So it looked like being the long way round. Ho hum.

My rope would not reach the roof, but fortunately the drainpipe did. The last time I shinned up a drainpipe, I was not prepared. This time I was. And the pipe was good stout cast iron, which gave me a firm grip and which I could trust not to bend. As I ascended, eighteen careful inches at a time, I listened for signs of recognition, but none came from inside or out. I’d reached the first floor when I began to discern – well, noises from within. Strange noises, which I could not place. I remembered that the window I was passing belonged to the Superintendent’s bedroom and drawing level with the sill, I peered through a chink in the curtains, and almost lost my purchase.

All I could see was a huge male fundament plunging and leaping like a crazy beam engine. But there was another in there with him, rising above the furious creaking of bedsprings – a female voice which I recognised as Matron, although not the Matron that I knew.

“Oh, God – oh, God – “

The metronomic, tortured groaning of the bedframe suggested that she was indeed being exorcised, with the brutality that I was used to when the Superintendent had wielded his cane. It was strange, but I’d never thought of Matron as being particularly religious, although I’d received too many bats around the head from her hairbrush to care if she was dying.

The important thing was that they were both distracted, and would not relish being interrupted by anyone who did chance to see me. I continued up to the roof where my crowbar served another use, to jemmy open a skylight. This admitted me to the loft space. Luckily, there was enough residual light trickling in from the streets to show me any obstacles between myself and the stairs.

I stole down three flights, past dormitories exhuding catarrhal snores to reassure me that I was as yet still unobserved. I was about to dip down the last flight to the basement, when a steady, measured footfall approached me along the ground floor corridor.

I froze. It was Jeremiah Thudd, the night watchman; a figure of dread amongst those who, for any private purpose of their own, were about after lights out. Seventeen stone of whalebone and sinew, with a further three stone of beer and potatoes; Mr Thudd was notorious for having exchewed the more traditional knobbly cudgel for three feet of lead piping as a patrol companion. As overnight surveyor of the workhouse assets, he took his trust very seriously and anybody falling foul of his leaden companion in an attempted midnight raid of the kitchens, was announced to have “fallen down the stairs.”

I caught my breath. Jeremiah was not known for his subtlety; had he suspected that anybody was about, he’d have gone for me. I tried to remember – he made regular rounds throughout the night; did this one include the cellar?

The footsteps hesitated and a beam of oily light shone down the steps, flicked from side to side a couple of times, and went away, accompanied by the softly heavy footsteps. Jeremiah was satisfied.

My breath stilled, I followed his departure with my ears until I could be sure of continuing safely. Floating down the stairs like I imagined a spirit would, I found the door locked. But I had expected this, and half the workhouse knew how to circumvent that old lock. They’d hoped to deter the passage of wrongdoers by making it big and heavy, but all they’d accomplished was to provide me with a lock which I could all but climb through. Risking a candlestub I’d brought with me, half a minute with one of Mr Whybrow’s small screwdrivers persuaded the inwards to cooperate, and the cellar was all mine!

It was not difficult to remember what was kept where, in the cathedral-like vault. Officially, only a few personnel were allowed down there, and they were all in on the smuggling game. So anything illegal was kept in a corner by the stairs to the side door, where it could be moved out quickly. But I thought it would be a good idea to buy myself some time, in case Jeremiah took it into his usually limited imagination to vary his routine. I’d brought with me a ball of twine – not that I’d foreseen a use for it, it just seemed sensible to take a ball of twine with me. But anyway, I ran a tight line from railing to railing at the top of the stairs.

There. Now, I didn’t want to risk lighting the gas, but they did keep a couple of lanterns handy in case roadworks should disconnect the gas supply at the wrong moment, and – ah, here we are. A pinch to trim the crud from the wick, another match, and I had a glorious light all to myself!

The cellar looked to the world like the hideaway of an industrious but unsuccessful smuggler. Old bedsteads, old furniture that nobody had got around to mending – and one untidy lump lurking in the far corner under a tarpaulin, which officially Did Not Exist.

Dear God, don’t let him have switched to brandy or tobacco – let it be silksilksilk………

I was almost afraid to throw back the tarpaulin, but knew I had to get on with it. The less time I spent in the cellar, the better. The old marine-grade canvas was heavy, but with a lot of yanking and tugging, I freed enough to reveal several barrels, cases of cigars, and -

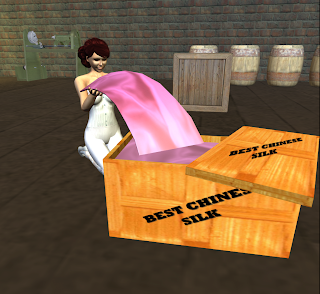

Yes!

Three cases of silk. Well, I should only need one. Silk, I knew, was very economical with space and that one case probably held enough to take care of my airship on its own. Standing my lantern down, I grabbed at the corner of the most accessible case and tugged it free. It made a grating noise on the flags, like Uncle Arthur escaping from his own tomb, but that could not be helped with so much other stuff standing on it.

It was only when the crate was free, and its weight diminished not a jot, that I realised that it wasn’t going to be so easy after all. Silk, densely-packed for transportation, was as heavy as lead; it was like trying to move an occupied coffin single-handed, without the benefit of handles on it. Silly tart!

Luckily, the outside door was not far away, just up another flight of steps, and like the other, sported a lock that could withstand a cannonball, but not a shopgirl with a small screwdriver. With the aid of my lantern, I had it unlocked in a trice and set to lugging the crate up the steps. Well, not so much lugging as dragging by one end.

I was about to open the door when I heard a clink of keys unlocking the door at the other end of the cellar. Jeremiah! I damned my foolishness at having been so engrossed in what I was doing that I had not heard his footsteps. Dousing my lantern, I stayed stock still, hoping that his feeble light wouldn’t reveal that the contraband had been disturbed. Or better still, that he’d just stick his head around the door in a token surveillance, and go away again.

Lady Luck gave me a rude gesture and stood back to admire the results. The door crashed open, and there stood Jeremiah, silhouetted behind his lamp.

“’oo’s dahn there?”

Silence. I dared not even breathe.

“Come on, I know yer dahn there. Come on aht, where I can see yer.”

He could have been bluffing, of course. I tried to edge further into the shadows without making any conspicuous movement. And then, of course, a rogue dust mote, imparted life by my manhandling of the tarpaulin, had to find the most sensitive part of my nose to settle and bore in something sharp.

And it had to happen in the moment of silence that Jeremiah had left, in order to listen. My sneeze broke the silence like an earthquake.

I stood there, paralysed. For an instant, Jeremiah’s lamp spotlit my face. Then everything seemed to happen at once as he took half a step downwards and discovered my tripwire. But instead of tumbling down the steps, he fell off-centre to plummet sideways over the bannisters. Letting out a cry like a rhino smitten with terminal constipation, he landed on top of an old grand piano which someone had donated, hoping to rid themselves of an instrument that had already died of natural old age while at the same time earning themselves public prominence for having Performed a Charitable Work. Naturally, the piano’s legs were the first things to give, dropping Jeremiah to the stone flags along with eight hundred pounds of frame, casing, and worst of all – over two hundred strings and their soundboard. I hardly had time to consider what that racket sounded like before a big old dresser, nudged by the piano, decided to take a bow of its own, and drop the workshop’s entire compliment of galvanised iron buckets and bathtubs onto Jeremiah and the remains of the piano.

My first thought was that Westminster Abbey had fallen down, complete with all its bells. Or perhaps an explosion in a boiler yard. My second was that between us, Jeremiah and I had just aroused the entire workhouse.

My third was that I was wasting valuable escaping time. I did not know how long it would take Jeremiah to extricate himself, but the persistent clanging from the darkness as his mighty arms flung ironmongery about told me that he was uninjured and I did not have forever.

I don’t know what lent me the strength to drag that crate up the stairs, probably just sheer desperation. But the silk bumped up one step at a time until I was at the door. I threw it open, and now that my eyes had adjusted to the poor light I saw what I’d missed when I went haring off up the drainpipe. A porter’s trolley – you know, one of those L-shaped things they use at stations. Suddenly, fate was smiling again.

Clumsily, I rolled the crate onto the trolley’s platform, and threw all my weight into a manic rush across the courtyard, the trolley’s iron wheel rims adding to the infernal blacksmithing pandemonium coming from the cellar. Gawd, I was all fingers and thumbs as I tried to pick the gate lock. I tried to ignore the workhouse stirring into life at the cacophony Jeremiah had unleashed – oh, all right, so it was my fault really. But the important thing was that that part of my awareness I could spare for my surroundings, told me that any attention inside the workhouse was being focussed on the cellar. Not on myself.

This particular lock was being a little stubborn, although it was probably just my nerves hampering me as I shoved, twisted, and jerked my probe one way or another. I expect it was less than half a minute before the tenon slid back with a satisfying “clunk” although it seemed like forever.

I flung the gate open, just as the first police whistle went up. Fortunately I kept the presence of mind to stick my head out into the street and listen, but I need not have worried. The thundering police boots ran along Gray’s Inn Road, straight past my turnoff. Naturally, the police had gone straight for the main gate. Which was their mistake, and my good fortune.

The crate took some heaving into the sidecar, and splayed out the wickerwork alarmingly – I hoped it would settle back to its original shape, or I’d have some explaining to do to Mr Whybrow. But finally, I got it settled into a position from which I could be sure it would not fall out.

I braced myself to bump-start the engine, hoping it was still hot enough to fire first time, when inevitably, someone shouted from a window that was overlooking the yard and the gate which I’d left open. I’d been spotted.

I was about to start tweaking and twiddling things to start the engine when I realised I’d not yet replaced the rotor arm. That was another minute of frustrated fumbling as I wrenched off the distributor cap, dropped the pesky little rotor arm into the gutter, clapped about trying to find it in the dark –

I’d just put the distributor cap back on when I realised that the cacophony in the cellar had stopped, to be replaced by another – this time of voices. That thick beery sort one associates with policemen, with Jeremiah’s plaintive whining trying to override them. I could not pick out individual words, but it sounded like he was trying to convince them that he’d broken every bone six times over.

It was no time to hang about. Choke – try half closed, petrol – on, and heave!

It was like pushing against a house. I wondered if I’d got a wheel stuck in a rut, but then realised it was simply the weight of the silk holding me back. The familiar crunch of police boots emerged from the cellar, to sprint across the courtyard. I hurled myself at the handlebars and, glory be, the bike started moving. Slowly, reluctantly, but gaining speed with every step that I took. I heard the gate fly open behind me, and a voice called out.

“Oy! You stop right there!”

I was not going nearly as quickly as I’d have liked, but I’d have to chance it. I vaulted into the saddle, and to my surprise, the Dreadnought did not slow up the instant that my impetus was removed – of course, that heavy great crate of silk; its extra weight was acting like a flywheel!

I let the clutch out and the motor shuddered, backfired once, and picked up eagerly; so eagerly that had I not kept a firm grip on the handlebars, I’d have been left behind.

Pausing only to swing out onto Gray’s Inn Road, I left a chorus of police whistles shrilling behind me. I turned left, instead of right as I should have, as this was easier – I didn’t have to cut across High Holborn. But it was no difficult matter to work across the residual night traffic and turn around, and I was able to relax as the Dreadnought lumbered happily on its way. Being Mr Whybrow, he’d given it a big enough engine to manage the extra load, although on reflection, my cargo probably weighed less than he did. It was just more awkward to grasp (and given his aloofness, I’m not sure that even that is true!). As I made my way past St Giles’ church, a policeman on the pavement waved his arms at me. They couldn’t have spread word about me already, surely?

No. Silly me. The lights! I flicked the switch, spotlit the constable, and he seemed to relax. What I thought of myself in that moment is not fit for these pages but then I was a little overwrought.

The wonderful thing about London was that it was no unusual thing to see someone with a crate in a sidecar at one o’clock in the morning, even if motor bikes weren’t that common a sight yet. I felt the stresses and worries filter away behind me as I cruised down Park Lane. I even allowed myself a chuckle at how I imagined the Superintendent’s face would look when the staff started hammering on his door. He would have a lot of explaining to do.

When I arrived back in SouthEnd, I let the Dreadnought take the last few yards at an idle. Mr Whybrow lived too far away, specifically upwards, to be woken, but there were always the other residents. I wished Mr Whybrow had thought of investing in a trolley as I heaved, pulled and otherwise manhandled the crate to the the cellar steps.

By the time I had the crate on the cellar floor, and the Dreadnought was tucked up for the night, it was three o’clock. I should have gone straight to bed, but my mind was hyperalert after my escapade and I just had to look at the object of all my trouble. Pausing only to chuck my sweaty fog-suffused overclothing into a corner, I crowbarred the top off the crate. I entertained a final worry that the contents might be something else mislabelled, but no. There it was, in all its glory. Hundreds of yards of the best Chinese silk.

And it was pink! Probably the least subtle colour to sport if you’re going to be floating under a cloud of it, but by an amazing quirk of coincidence, it even matched the airship gondola. Very well. Just as Mr Whybrow favoured his lush purple and gold on his vehicles, my own colour would be pink.

My nights were going to be busy and I had the buildy bug seething through my veins. I knew I could not sleep until I’d at least made a start at cutting out what I needed.

As I should have expected, the time flew by and when I stood up, most of the cutting-out done, it was nearly half past five. I tidied up, and on the way out, realised that I had the perfect opportunity to sneak a look in the yard at whatever it was that Mr Whybrow was up to. But I had to be up in less than two hours.

Oh, knickers!

Let him keep his secret for one more night. I needed sleep!

No comments:

Post a Comment